Tribal leader Joel Jackson of the Organized Village of Kake (OVK), a Native village in Kake, Alaska, plans to convert a disused USDA Forest Service building into a traditional healing center funded in part by Quakers paying reparations for Friends’ roles in Indigenous boarding schools.

Jackson, who serves as president of the Tribal Council of OVK, previously worked as a police officer in the village and had to respond to 15 suicides during his last year on the force, he recalled in an interview. He attributes such loss of life, as well as other maladies, in part to destruction of Indigenous culture by European settlers.

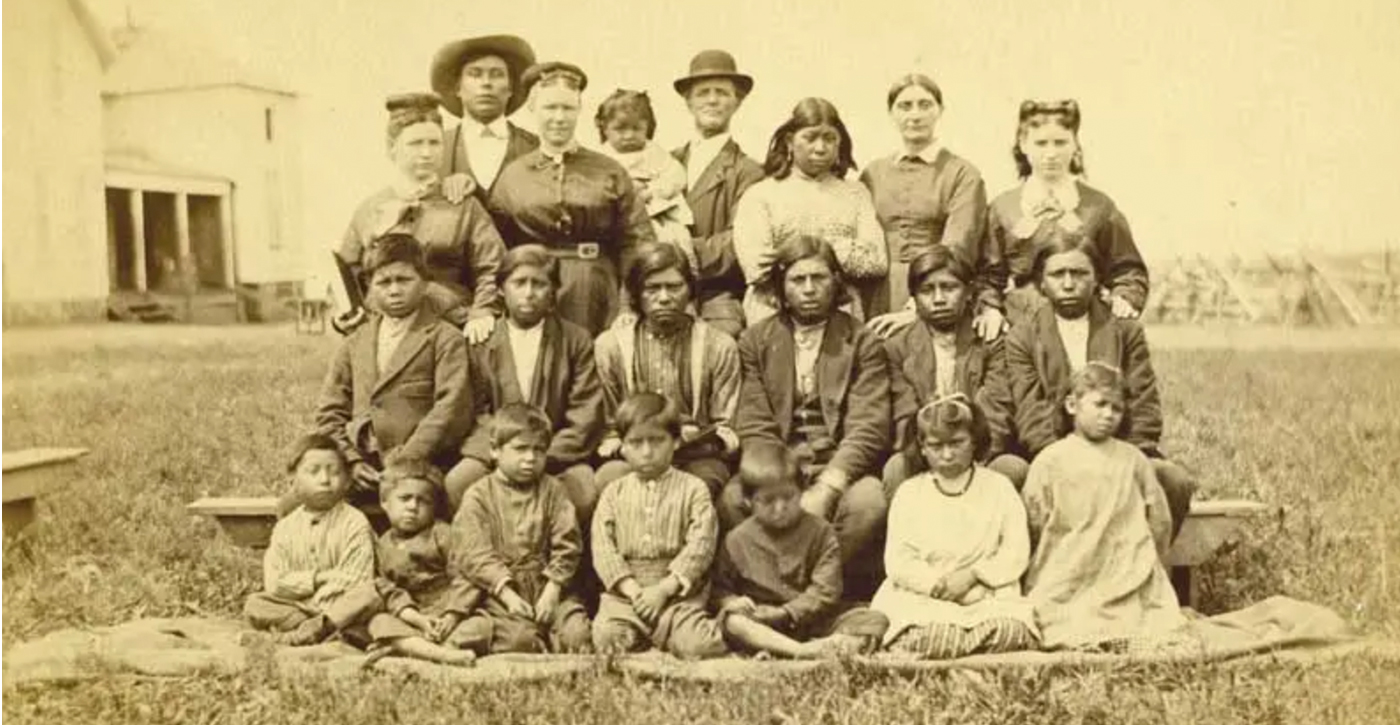

Religious groups, including Quakers, operated boarding and day schools designed to assimilate Native American children by forcing them to give up their languages, religions, and lifeways. Students were often forcibly separated from their families and endured psychological abuse by teachers, according to Jackson. Many Indigenous children from Alaska were taken from their families and placed in boarding schools and orphanages in other states.

The U.S. federal government operated 408 Native American boarding schools in 37 states (or what were at that time territories), according to a 2022 report by the U.S. Department of the Interior.

So far, Quakers from three states have contributed $93,000 in reparations to support the healing center. After listening to testimony from family members who still experience harm from their relatives’ time in Quaker-run Indigenous boarding schools in Alaska, Friends from the states of Washington and Oregon allocated $75,000 in reparations, according to Jackson, referring to an allocation by Sierra-Cascades Yearly Meeting of Friends (SCYMF). Alaska Friends Conference (AFC) paid an additional $18,000 in reparations; the check was delivered in person in January.

SCYMF offered the reparations as part of a longer process of lamenting past harms and seeking right relationships with Native people, according to yearly meeting co-clerk Norma Silliman.

“We still have a lot to learn and our work has just started,” Silliman said.

In June 2022, SCYMF adopted a minute opposing the Doctrine of Discovery, a 1493 papal decree stating that explorers supported by the King of Spain could claim land even if it was already inhabited, provided that the residents were not Christians. The minute affirms SCYMF’s commitment to making restitution for historic Quaker financial support of and staffing of residential and day schools in which teachers sought to forcibly assimilate Indigenous children. The minute states that the schools were part of a broader campaign of genocide, land theft, and forced assimilation that people of European descent committed against Indigenous inhabitants of Turtle Island, also called North America.

SCYMF was previously part of Northwest Yearly Meeting (NWYM) before disagreement about LGBTQ+ rights led to a separation in 2017. Oregon Yearly Meeting, the predecessor to NWYM, supported an Indigenous day school on Douglas Island, on Tlingit land, in Alaska. Quakers also administered a government-sponsored day school for Native Alaskan children in Kake for several decades.

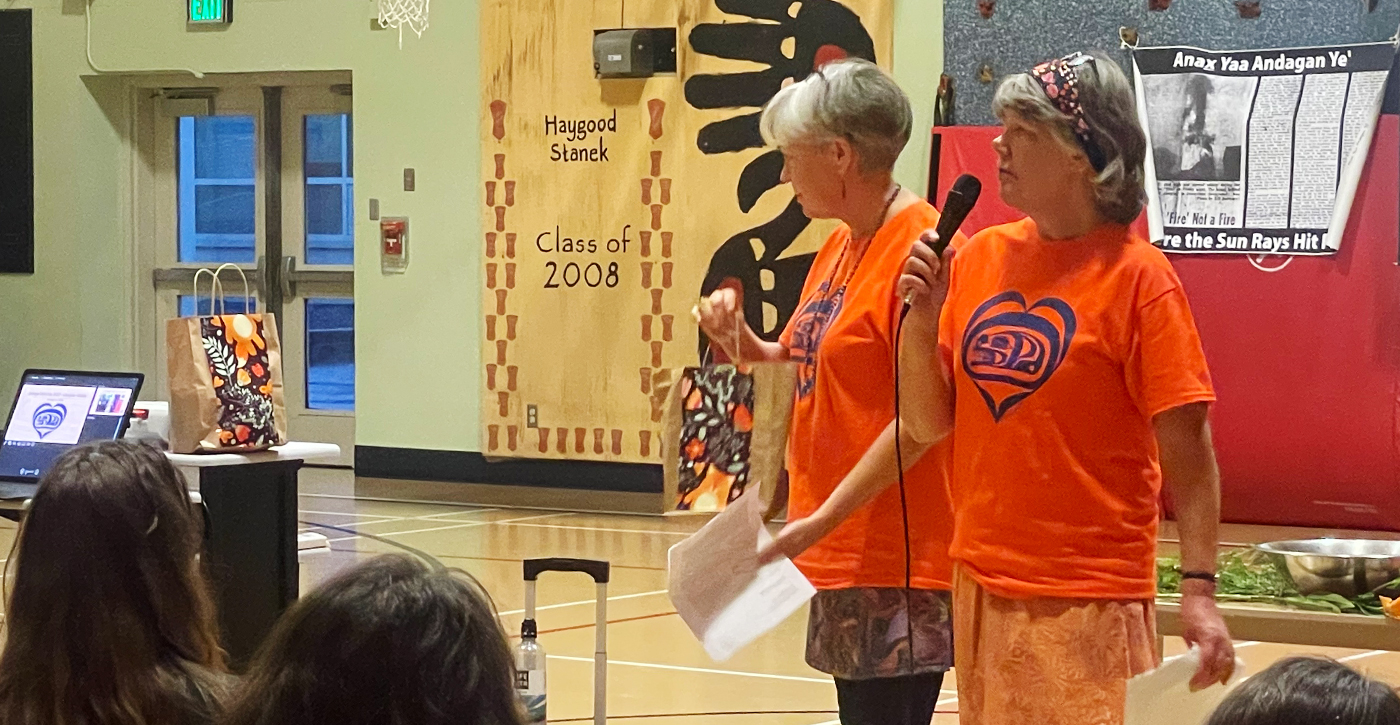

The payments follow a 2022 public apology from AFC read by Cathy Walling, a member of Chena Ridge Meeting in Fairbanks, Alaska, and Jan Bronson, a member of Anchorage (Alaska) Meeting. Walling and Bronson declined to comment for this article. In an email to SCYMF thanking the yearly meeting for its gift, they wrote:

Alaska Friends Conference members continue to be inspired and in awe of the various ways that we are called to take the next step toward right relationships with Indigenous peoples! Sharing this journey with Sierra Cascades Yearly Meeting of Friends is one of the rich gifts we have experienced.

One person who offered testimony to SCYMF Quakers was Jamiann S’eiltin Hasselquist, who works as a regional healing catalyst for the Juneau-based anti-violence nonprofit Haa Tóoch Lichéesh. Hasselquist belongs to the Raven Beaver clan, of which the dragonfly is the house crest. Her mother was a student at the Sheldon Jackson School, a residential school in Sitka, Alaska, operated by Presybyterians. Her aunt and uncle were also Indigenous boarding school students. To prepare herself spiritually and emotionally to testify about the harm committed at the boarding schools, she went to the water to cleanse herself, spent time alone preparing her presentation, and enlisted the help of trusted supporters, she recalled in an interview. She testified at SCYMF’s annual sessions last June in Monmouth, Ore., speaking about how the schools took away Indigenous language, culture, and ways of life. Wearing traditional clothing was outlawed. As Hasselquist spoke, two supporters put wrist bracelets on her, which signify tribal identity. During the period when it was illegal to wear traditional attire, Native Alaskans wore bracelets that expressed their identities.

Jackson’s parents were also students at the Sheldon Jackson School. He has long seen the need for a cultural healing center to connect Native Alaskans with traditional practices boarding school staff tried to erase. The center would support people recovering from alcoholism, depression, and other health concerns.

“I’ve always wanted to open one to help our people who are suffering from intergenerational trauma and boarding school trauma,” said Jackson, who cofounded an Indigenous culture camp in Kake that is entering its thirty-sixth year.

The healing center would provide care, traditional activities, and connection to the land. One Indigenous healing activity is to gather medicinal plants, according to Jackson. Another example of a healing practice is to learn about traditional hunting, bring a deer or moose to the facility to process, and share it with the community. Fishing can also be a healing practice.

Jackson is currently looking for an insurance company that will insure the building, which is in a remote location about 50 miles from Kake. The building, which formerly housed Forest Service employees who thinned and timbered the woods, has eight bedrooms and two bathrooms, with electricity and running water. The reparations money will be used for insurance as well as work on the building, which requires cleaning and painting.

Jackson plans to hold a ceremony to bless the building, possibly this summer. The ceremony will include a cookout with traditional foods as well as tours of the building.

He is also exploring whether Medicaid and Medicare could be used to fund Indigenous healing practices. Certified Indigenous healers will staff the center.

“Most of it is how well you know your culture, how well you know your traditional medicine,” Jackson said of how traditional healers qualify for certification.

After seeing the building on a drive with his brother, Jackson called the regional forester, an acquaintance from Juneau, and explained his vision for the space. The forester enthusiastically embraced the idea.

“The Forest Service supports Indigenous-led endeavors promoting healing from intergenerational trauma and other hardships. Our country has a history of federal–tribal relations fraught with injury and injustice. Our agency is committed to a future of strong healthy tribal relations that are mutually beneficial for tribes and the federal government,” said John Winn, a Forest Service spokesperson.

The Forest Service plans to issue a special permit to allow the Organized Village of Kake to use the building as a healing center, according to Winn. The Forest Service does not plan to sell or transfer ownership of the building.

Jackson and Hasselquist consider the reparations payments and the center a beginning of what they believe should be widespread healing. Hasselquist would like to have an Indigenous healing center in Juneau. She wants to inspire Friends across the United States and Canada as well as non-Quakers to learn about their own history and their forebears’ participation in the harms of the boarding school era.

“This isn’t just one-sided. I don’t think we can heal alone,” said Hasselquist.

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.