Returning to the Faith of My Ancestors

In the small village of Orchard Park in western New York State, the Quaker meetinghouse provides a haven for those seeking quiet community in troubling times.

About a half mile east from the center of Orchard Park, along a stretch of Route 20A that is designated Quaker Street, a 200-year-old white two-story building stands silent and meditative among locust, sycamore, and maple trees. The inset gray porch holds one empty chair framed by two doors. A cemetery borders the east and north sides of the grounds. More dead souls than living ones populate the grounds. Every time I visit my cousin Denise, I pass the meetinghouse, noting the sign outside announcing their presence, even though I never saw anyone.

I’d first become interested in learning about Quakers after using my summer break from teaching to dig deeper into my Weaver ancestry, discovering that in the 1600s the Weaver men—who never became Quakers themselves—began marrying Quaker women. One Weaver even fought in King Philip’s War during 1675, an act that seems antithetical to what I knew of Quaker, or Quaker-friendly, actions. How could he justify violence with a pacifist wife? Don’t Quakers uphold peace? Maybe I had the image of Quakers—simply dressed, quiet, antiwar relics of history—all wrong.

A quick Google search yielded basic yet unsatisfying results: they were Protestant; the movement began in 1600s England; they believed in direct messages from God. Quakers were guided by advices and queries: messages and questions to consider in silent worship. Another search revealed a meme created using a pencil sketch of Quakerism’s founder, George Fox: donning a slightly floppy cap and a white neckerchief, Fox looks upward as if toward heaven, his hands slightly raised in front of his torso. The words “History teacher thinks I’m extinct” frame his portrait.

I decided I had to attend a meeting, so I texted my cousin who responded within seconds that she would go with me. I prepared myself by reading about, in general, what to expect. Members sit for an hour in quiet meditation, waiting for messages. When compelled, members share a story or a message or a thought that occurs to them in the moment. I remembered a scene in the TV show Fleabag where Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s character attends a Quaker service. It looked painfully uncomfortable, her character blurting out a message about her breasts and feminism in one of the more cringe-worthy scenes. I was terrified. For someone drawn to solitude and quiet, I was nervous about how long an hour would feel when I was silent among strangers.

What could, or would, I say?

The August sun, even at 9:30 in the morning, beat down from the sky. My heart raced with nerves. I blasted alternative rock, my Jeep’s windows rolled down and my arm hanging out the side, until I reached Quaker Street. I turned down the radio as the tires crunched slowly along the meetinghouse’s circular, unpaved drive before parking adjacent to the white wooden split-rail fence along the building’s western edge. Denise was already waiting for me. We giggled, still ten years old when we are together, self-consciousness and nerves getting the better of us. Our slow pace, dictated by Denise’s post-stroke limp, steadied our breath.

We entered the front door to smiles and hellos, numerous introductions. I let my cousin do the talking.

“Yes, I’m Denise. This is my cousin.”

“How wonderful. Nice to see you.”

A second voice chimed in. “I’m sorry, what are your names again?”

This time I answered with my name.

“We’re just so glad you could join us this morning.” Each wizened face smiled at us as we made our way through the anteroom and into worship.

Rows of raised benches faced each other; a few gray, padded steel chairs dotted the rows. I gazed up at the quilt-covered balcony, which I read can hold up to 300 people, though I didn’t believe it. We sat on a bench on the right side of the meetingroom. People entered, maybe nine or ten, and a small, silver-haired woman started the 11:00 a.m. meeting with a reading, saying that those present were welcome to hold it in our focus during meditation. I couldn’t concentrate on the words, only her description of the author, the Choctaw elder and Episcopal bishop Steven Charleston. Another woman fumbled a bit with a laptop before two Friends appeared on screen through Zoom.

Members’ backs hunched in unison. Most closed their eyes. A few, I’m convinced, drifted off here and there, their bodies slouching further, occasionally swaying.

After a few minutes, I stared at the floor and then peered out the window. The glare of the sun and the heat in the room made me think of the dwindling of summer: how the first week of August heightens a nostalgic ache in my stomach as I anticipate the fall, and that winter would be coming soon enough. I thought about the start of my teaching year. I thought about a research fellowship I had been on earlier in the summer.

I sneaked a glance at my watch. Only 11:30.

I looked, again, out the window. The sun shimmered against the leaves that shook, subtly, in the breeze, the greens moving in the shifting sunlight, under a blue sky spattered with cotton clouds. I’d checked the weather earlier and remembered that in nine hours the sky would change, the clouds would grow more threatening, and the heavens would pour rain down, chilly and damp.

“That’s one thing that Quakerism has taught me. Violence isn’t just shooting, or something like that, but there’s a violence of our minds. And that is what we consider. That is what our meeting silence is for.”

A few Sundays later, I jumped out of my Jeep and right through the front doors: comfortable now, confident in knowing what to expect and where my thoughts would take me, which was usually my mental to-do list punctuated by staring out the four-paneled windows waiting for autumn to fall. This morning the trees were still a brilliant green, and though the air held hints of changing seasons, the leaves hadn’t yet left the trees bare and exposed.

The clerk voiced that the meeting would begin, and my gaze shifted to the windows.

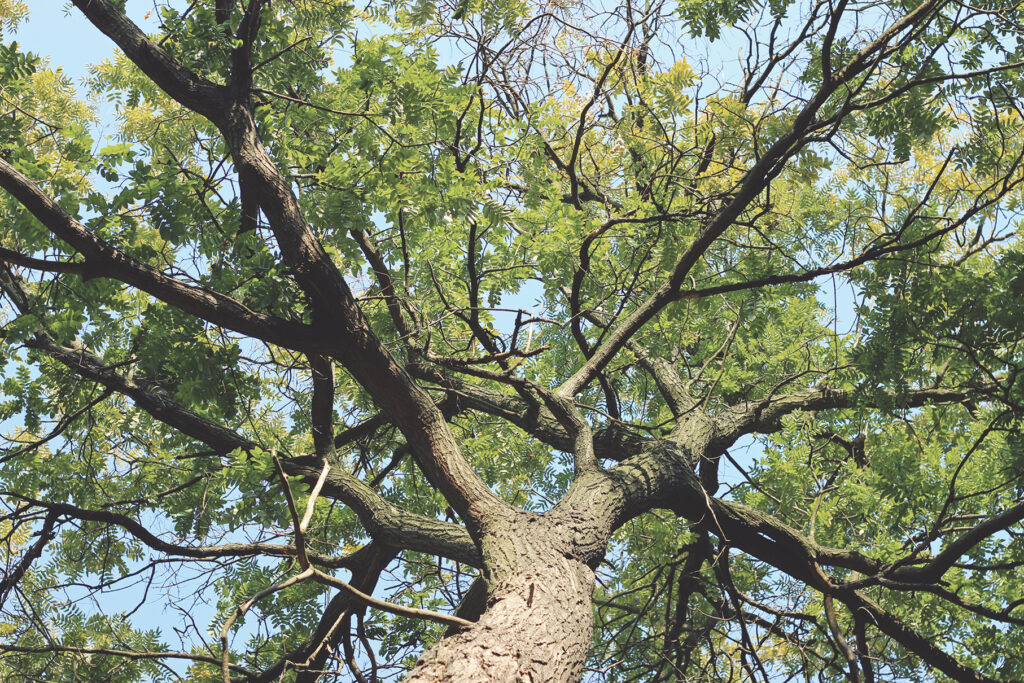

The trees reached high above the second-story window panes, the lush leaves silently swaying against the leaden sky. I’d made it a habit to eat toast beforehand so that my stomach’s growling wouldn’t be the message I delivered. This morning the heating system had been turned on, and, rather than my stomach, the unevenly timed tings and occasional clunks of the heater punctuated the silence.

A Friend who acted as a meeting historian, delivered the first message:

Quakers started about 1648 with George Fox. At that time, Quakers were called “Children of the Light” and “Friends of the Truth.” About 1690, Quakers began speaking of advices and queries, and people wondered what happens when they meet in silence. They wondered what revelations were revealed.

Another Friend spoke about advice read earlier about the abolishment of the death penalty. She spoke of how we are all serving a death sentence, our relationship to time, how we are so often not present. She thought having and accepting advices allowed us to act as opportunities arise, and sometimes floundering can happen when you do not have principles, beliefs, objectives. We needed to start by stopping; we needed to start by listening.

I scribbled furiously in my notebook, wondering how I observed and listened but didn’t really apply the Quaker tenets to my life. What are my principles? My beliefs? My objectives?

At 12:00 p.m., the clerk thanked us and asked for final thoughts. He listed the upcoming October events. On my way out, I noticed a newly planted Japanese maple directly opposite the front door. I hopped into my Jeep, driving slowly until I hit the speed of traffic on Route 20A.

I went for a run shortly before the October 15 meeting, which didn’t leave me time to shower and change. I jumped out of my Jeep slightly sweaty but no longer panting. I sat in the anteroom for a few minutes while an invited speaker finished her talk about working with disabled children. Nine people eventually gathered in person, and two more joined on Zoom. I noticed a man in a Harley Davidson jacket. What kind of Quaker rides a motorcycle, I thought.

There were only two messages that morning. One spoke about war and atrocities in Gaza and Ukraine. The speaker brought up the question many people think of: how can God allow this? “Quakers believe in the God within,” he explained. “In the Bible, once you leave the garden and learn, you’ll look past the animal nature of man, and you’ll find your connection to God. Then you must strengthen it.” “Look for God,” he said. “But even when we find him the work isn’t done.”

The man in the Harley jacket spoke about how he thought sending personalized postcards to our government representatives would get their attention. People ignore scripts but pay attention to personalized, well-written communications, he reasoned. That’s what he said he would do later that night.

We spent the remaining time silent.

Denise and I walked out of the meeting with a man in his early 50s with thinning hair in a short ponytail at the nape of his neck, graying along his temples. He had been an attorney for a while, long before he began attending Orchard Park Meeting, and he lives about 20 minutes away. He’d started attending these meetings eight months ago. I asked him what his experience had been like so far.

“It’s just great. These people are just so . . . ” He paused. “Well, nice. They’re just so darn nice. Nothing like what I’m used to.”

I asked him what drew him to Quakerism.

He chuckled. “In the third grade, I remembered learning about Quakers not taking their hats off to the king, and that just stuck with me.” He put his right leg up on one of the steps. “And I started doing a little genealogy, and I discovered that one of my ancestors was a Quaker: Elizabeth Webb, who had a whole book written up . . . something about dream speeches.” He smiled. “You know there was a whole dissertation written about her book!”

We heard the screen door open and turned to see the clerk smiling at us. “So good to have you all here.” The four of us briefly talked about where we lived, the beauty of Orchard Park, and that it was time for lunch.

I’d emailed the clerk one Sunday morning, and he responded three days later, saying that it would be best to talk on the phone and gave me his number. When I asked him to tell me about the meetinghouse, he didn’t stop talking for 25 minutes.

He talked about how in the 1950s, a minister from the nearby town of Collins noticed the meetinghouse wasn’t being used, learning it had been that way for 14 years, so he began helping to reinvigorate it. He talked about how they believed, but couldn’t prove, that the meetinghouse had been a stop on the Underground Railroad. He talked about how he came to the meeting because of Vietnam, how he’d been on his way to being a conscientious objector, about waiting out the draft for a year, about the Berrigan brothers—priests Daniel and Philip, who he described as a little miracle when they him know that he could object to the war, that he didn’t have to fight—and how he moved from Catholicism to Quakerism shortly after that, about how Vietnam led him to the Society of Friends. He talked about how young people have come to meetings, but the lonely older folks sometimes come on too strong: they spent much of their time alone and would jump on new people, scaring them off; he spoke about how the meeting members have been reaching out to other faiths through a local church collective called Park Parsons. He talked about a young Quaker who attended an Evangelical, fundamentalist Kenyan meeting that overwhelmed her, but she told him something that stuck with him: she told him that she learned to grow up and accept people.

What that young woman said resonated with him. He has a conservative son-in-law in Tennessee with whom he disagrees on nearly everything. But the last visit he had with him was wonderful, and it wasn’t because the son-in-law changed. He did.

“That’s one thing that Quakerism has taught me.” He paused. “Violence isn’t just shooting, or something like that, but there’s a violence of our minds. And that is what we consider. That is what our meeting silence is for.”

The Orchard Park Meetinghouse, like the locust tree, remains a silent strength for its small number of devoted Friends. And, maybe, that’s what has kept the Meetinghouse around for 200 years.

I never spoke at meetings, but one time my cousin did. It was a week when only five attended. No one had spoken during the hour of worship, but when the designated clerk that week closed the meeting and asked if there were final thoughts, Denise finally found her voice.

“You know, I didn’t want to say anything to break the silence, but I’ve been looking out the window at that locust tree.” She waved her arm in the direction of the tree. “I’ve always hated locust trees, and I was just complaining about one in my yard. Just hate it. The locust leaves just get everywhere and they’re the worst.” She giggled, then paused for a moment. “But this morning I’m thinking something different. I’ve thought about how hardy the locust tree is and how it always survives. I’ve got a different perspective on it now.”

I, too, now have something to say.

Sometimes Quakers come to meetinghouses through their individual ancestral ties, and sometimes they come as an act of resistance. Quakers gather in their peace and their protest to King Philip’s War, the Vietnam War, or today’s wars in Ukraine and Israel–Palestine; Quakers gather to aid others toward peace and protest, such as through the Underground Railroad or global missions like Friends of Kenya Rising.

The Orchard Park Meetinghouse, like the locust tree, remains a silent strength for its small number of devoted Friends. And, maybe, that’s what has kept the meetinghouse around for 200 years. They know that their low numbers are irrelevant to the big picture, and they honor the knowledge that as war and strife rage outside meetinghouse walls, they must find their own quiet, their own solace. Their silent steadfastness is their most profound message.

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.