How Does That Impact Quakers Today?

We, Naveed and Johanna, are participants in the Quaker Coalition for Uprooting Racism (QCUR). QCUR is a nine-month hybrid program that helps people to challenge white-supremacy culture. During a class homework assignment, we each researched George Fox’s trip to the English colonies in 1671. We were moved to write this article as a result of what we found.

While writing this essay, we examined Fox’s Journal, primary-source letters, and many interpretations of his ministry. We often wondered: How did Fox’s actions contribute to patterns in the present day? We practiced “noticing patterns of oppression,” a concept that comes from Niyonu Spann of Chester (Pa.) Meeting. Many Friends have learned this practice from Niyonu and her work in many diverse Quaker spaces.

We recognize that our racial identities affect what comes up for us when we learn about Fox’s past, so we’ve decided to speak from our individual voices in this essay.

Naveed:

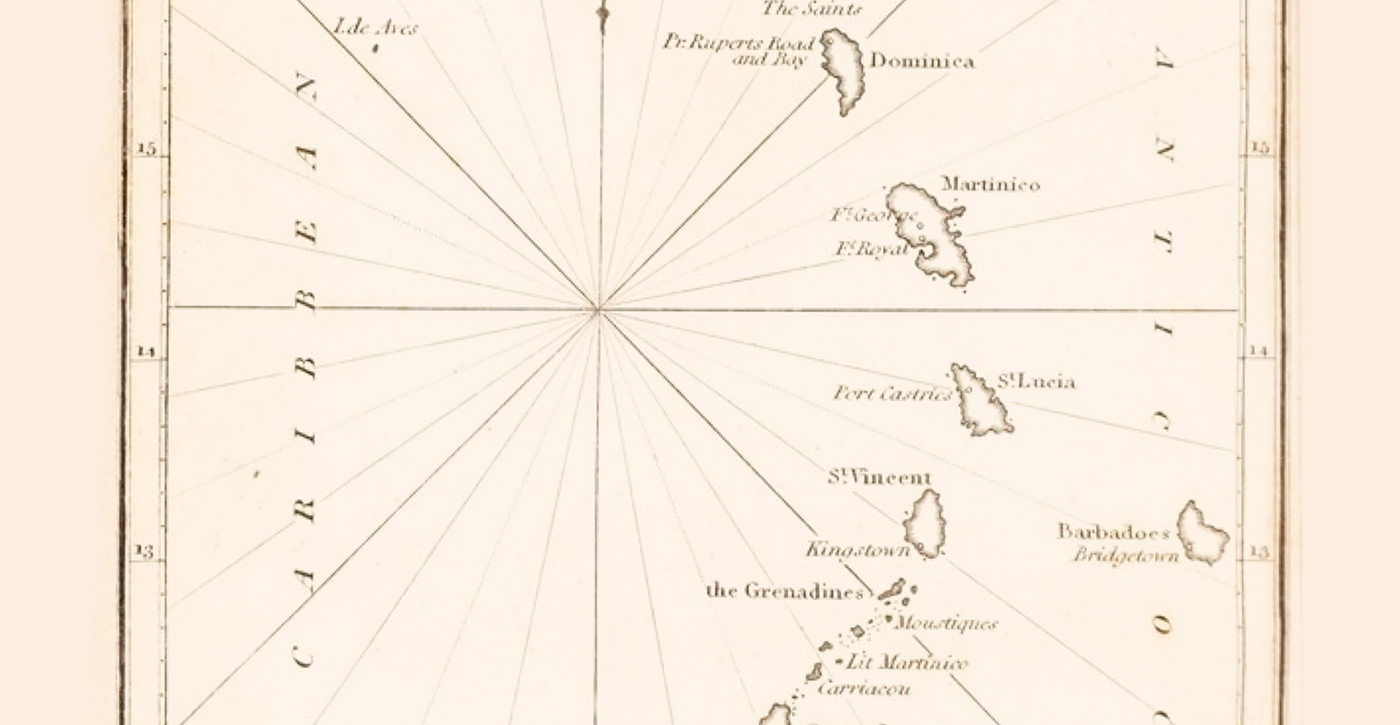

In 1671, Fox undertook a journey to the English settlements in the West Indies and America, and remained there for two years. He was joined by almost a dozen Friends from England. Why did he travel so far in the ministry? Speculations differ wildly in accounts of Fox’s attitude while he was present in the Western Hemisphere. However, in all accounts and interpretations of Fox’s visit, one thing is very clear: he wanted to establish more monthly and general meetings. While he was abroad in the colonies, he was greatly troubled by Quakers not comporting themselves according to right order.

In learning this, we asked: how did Fox’s narrow mission influence how he traveled in the ministry? What influence did he have on those he spoke to?

Johanna:

During his journey, Fox became incredibly ill. His joints ached; his body was parched; he was sometimes too sick to speak. After arriving in the West Indies, he took one month to recover. He relied on Quaker hosts for medical care. Later, Fox visited Quakers and preached. He encouraged Friends to keep records of birth and death. He defended the boundaries of marriage, telling people to avoid child marriages and polyamory.

At the time of Fox’s visit, Barbados had more enslaved people than free people. According to his Journal, at one point Fox attended a meeting for worship at a plantation that enslaved at least 200 people. What did Fox do to stop slavery in Barbados? I was surprised to learn that he did almost nothing. I wondered: what was happening—with Fox’s health, with his clarity—that kept him silent on such a critical issue?

Naveed:

At nearly every place he stayed, Fox would have been in the presence of enslaved people. While in Barbados in 1671, he had cause to write a letter to the authorities, which has been titled “For the Governour and his Council & Assembly.” This was written after a number of Quakers had been accused of “encouraging negroes” to rebel. In the letter, copied later in his Journal, he says that Quakers “[exhort the Black People] to be sober & to fear God and to Love their masters and mistresses, and to be faithful and diligent in their master’s service & business; & that then their masters & Overseers will love them and deal kindly & gently with them.”

Johanna:

In this letter, Fox assured the governor that Quakers had no interest in disrupting the order of things. He wrote: “Another slander and lie they have cast upon us is, namely, that we should teach the negroes to rebel.” He said that this was “a thing we do utterly abhor and detest in and from our hearts.” He further defended: “The Lord knows it, who is the searcher of all hearts, and knows all things; and so can witness and testify for us, that this is a most egregious and abominable untruth.” In some ways, Fox could not have gone further to side himself with the status quo.

Fox did go further, though. In the same letter to the governor, he compared enslaving people to running a household. Fox wrote: “[I]t’s no transgression for a master of a family to instruct his family himself, or else, some others in his behalf.” After all, he reasoned, Abraham and Joshua instructed their households in biblical times. Indeed, it was a patriarch’s duty to admonish and pray for family members. Fox’s letter continued to normalize slavery. Fox relied on Old Testament thinking as an excuse to stay quiet.

Naveed:

The rest of Fox’s letter focuses on how the spiritual salvation of the enslaved is a responsibility for the master. In our process of examining this point in history at QCUR, we thought about the present moment: How does this belief perpetuate a behavior among Quakers today? In what ways do white Friends today feel the need to be saviors?

Johanna:

According to writer and producer Nova Reid, a white savior is someone who has an “impulsive desire to fix, to be the hero of the story, to swoop in and rescue.” Among Quakers, one example of white saviorism was nineteenth-century support for Indian boarding schools. Quaker staff taught children to be ashamed of their bodies, identities, and families. They intervened aggressively, creating generations of trauma.

When I hear white Quakers say “We want more Black people in our meetings,” I understand that to mean “I would feel more comfortable if our meeting looked more diverse.” Or: “We, a mostly white community, have something that People of Color would probably like to have.” If you are a white Friend, consider the assumptions under those phrases.

In contrast, an epistle from Friends of Color in 2020 says: “Friends of Color need respite and support which our home meetings have not provided. Friends of Color are fatigued from being asked to teach white folks.”

Stepping away from white-savior thinking means letting God lead. This takes humility and patience. As Dwight Wilson, a Black Quaker minister, said, “If the Holy One is there in the room, the Holy One is the smartest.” From what we know, however, Fox did not enter Barbados with that kind of humility.

Naveed:

The widespread suffering of enslaved individuals would have been noticeable in many of the locations where Fox resided. While the issue of slavery in his native Britain was complex—with various conflicting judicial rulings documented in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries—both slavery and indentured servitude were present in Britain. However, statistics indicate that the prevalence of bondage in North America was higher than in Britain. Statistics from the meticulously recorded slave trade show that it was in fact increasing exponentially during that time. Had Fox condemned slavery, his stance might well have posed a challenge to those who were hosting him, as he strived to fulfill his primary mission of restoring order among the Quakers in the New World.

It may have been out of respect to his hosts that Fox was quiet on the issue. “Respect,” though, is a tricky word. Respect allows us to sit in silence and receive the messages of others rather than standing and interrupting. Respect opens the path to treat others with dignity, but respect can lead us to pave a road with good intentions that unintentionally cause harm to others.

Fox’s respect for his hosts might have paved the way to condone slavery and subsequently condone the Friendly brand of white supremacy that has been a hallmark of Quakerism for the centuries that followed.

For his time, Fox was outspoken and was prepared to be jailed for it. So why would he not be brave and outspoken when he reached the Barbadian shores? What held him back from making a strong proclamation? Maybe it was the same feeling we have when we don’t stand for the persecuted for fear of becoming the persecuted. Did he feel he could stand up for white Quakers but that standing up for enslaved people might be a step too far? I wonder if it is the same feeling that makes me fearful of posting about social justice on my Facebook page while I am unemployed, or speaking too loudly on the issue of Palestine and Israel as someone with a Muslim name. We become frozen, unable or unwilling to act.

Living in a frozen state prevents us from relating to “the other.” We look at those who are suffering, but we don’t really see them. They become part of the background, because there’s only a certain amount of trauma our cognition can hold in a moment.

In working through his cognitive dissonance—his frozen state—Fox sermonized on how we can all lift ourselves out of moral poverty. By acting in right order and coming to God, Fox, according to Quaker historian William Frost in his 1991 article “George Fox’s Ambiguous Anti-slavery Legacy,” “most often concentrated upon an individual’s responsibility in causing and ending sin. . . . Fox did not focus on the collective dimensions of evil.”

Johanna:

While focusing on individual choices, Fox called on People of Color to stay low. According to his letters, he instructed Black people to speak truthfully, to not complain, and to take only what is given. He told them not to steal, even though their lives had been stolen from them. In other words, Fox told People of Color to trust the systems that were abusing them.

The phrase I use for this is “out-of-order meekness.” Out-of-order meekness isolates some Friends from their spiritual gifts. It teaches some of us to accept our “station” in life.

In the present day, out-of-order meekness happens whenever a Friend reprimands a strong woman for how she uses her voice. It happens when People of Color run into delays due to meeting process. In three different parts of the United States, I have heard straight Friends say of a lesbian woman things like: “I’m not really sure she follows Quaker process,” and “She is kind of pushy.” A pattern of out-of-order meekness is to enforce different standards upon different people: being easy on white men, being hard on others. When I heard a meeting brush off a white man’s dominance as “just being Steve,” they avoided setting a necessary limit.

What is the antidote to this kind of behavior? What would it look like to liberate ourselves from it? The opposite of this meekness is bravery, clarity, and voice. We step into liberation when we are willing to interrupt harm. When a group from Earth Quaker Action Team worshiped inside of a bank lobby to protest mountain-top removal, that took bravery. When Benjamin Lay used fake blood to protest slavery at yearly meeting sessions, that did too.

Naveed:

In 1701, Philadelphia Yearly Meeting, the largest yearly meeting of Friends in the British colonies, chose to republish Fox’s Gospel Family-Order (published shortly after his trip to the New World). This writing implicitly endorsed the practice of keeping slaves; it exhorted slave owners to bring the enslaved closer to God. It gave permission for white Quakers to own slaves. It went as far as detailing the responsibilities that white owners have to control their slaves’ religious agency.

The selective publication of this tract reinforced notions of hierarchy, right order, and out-of-order meekness. It also reinforced the notion that Fox’s word was somehow more authoritative.

We have made great strides since the 1700s. Our perception of what is evil—particularly of how slavery and racism are evil—has taken huge leaps forward. But some of the lasting legacies leave Quakers frozen to this day. Individually and as a Society of Friends, we adopt patterns of behavior that perpetuate harm against People of Color. Being openhearted as a community leaves us vulnerable to taking on the world’s pressures. In resistance to these pressures—racism, capitalism, authoritarianism, and many other “isms”—we develop right order: behaviors that we feel will help bind us as a community. But have we considered the harm right order might do?

In 2017, Avis Wanda McClinton, a Black Friend, was “read out” of Upper Dublin (Pa.) Meeting. The corporate behavior of the yearly meeting put Avis through the pain of a long and drawn out process, one that did not necessarily lead to healing. The tacit acceptance of this was a reinforcement of both right order and out-of-order meekness.

Johanna:

When Friends can name a pattern of oppression, we have language to say what is not working. As I studied Fox’s actions, I found it helpful to break down the work into steps. First, I would identify a pattern of oppression, sometimes with the help of others. Then I would ask myself: What is the opposite of this pattern? Breaking things into small steps helped me see more clearly. Finally, I asked: Where do I see people living into that opposite?

As we shared before, we believe that George Fox was frozen into apathy. What is the opposite of being frozen? It could be staying present to pain in the world. It could be recognizing our limits and turning things over to God. It could be as small as sharing honestly during the joys and sorrows period of worship.

Naveed:

As a faith, we put great importance in being moved by the Spirit. Our worship consists of silence until we are moved to speak. But what happens when we remain silent, unmoved? There is a Latin phrase that was used during the trial of Thomas More in the sixteenth century: qui tacet consentire videtur (he who is silent is taken to agree). Following Fox’s visit, slave-owning Quakers persisted in North America, interpreting his silence as tacit consent to slavery, albeit with the caveat of treating slaves well and leading them to God.

George Fox was racist, and he perpetuated the notion of slavery. Friends reading this article may try to argue a way out of this, but the evidence is clear and we should embrace it.

This is not to make us complicit in perpetuating this travesty, as Philadelphia Yearly Meeting Friends were in 1701. What we are asked to do as Quakers is understand what it means to have leaders in our faith who are deeply flawed. The gift here is continuous revelation. In contrast to religions where revelation is confined to select individuals, our commitment to continuous revelation empowers all of us to reexamine what we accept as “received wisdom.” This approach allows us to test the leanings of earlier Friends and, if necessary, deviate from tradition. We should examine those behaviors and words of wisdom (“the way we do things” in our meeting or yearly meeting) that come from the way white folk did things in the past. How can we change them to ways that embrace everyone? How can we change our learned behavior to one that is just for all?

Thank you for this enlightening essay. Well done.

It seems to me as an archaeologist and historian, that almost everyone of note in the historical past held attitudes and was a participant in practices, such as racism and enslavement, that we find repugnant by current standards. When thinking about such people, it is important to understand them as products of their own time and place. I think in most cases it is necessary to have our eye wide open to the good and the bad, and try to weigh the totality of their actions and contributions when considering if it is appropriate to remember and memorialize such personages. We need to try to understand them as complex and sometimes contradictory in their attitudes and actions. Some will be remembered despite the evils they participated in or perpetuated, and others, perhaps fall into well-deserved obscurity.

Given Quakers were nearly banned out of existence in England until Fox guided Quakers to a pacifist non-threatening stance with the government, it’s not surprising he feared upsetting authorities and getting Quakers thrown out of Barbados. His first priority was to sharing God’s equal love as widely as possible without forcing conflict. It took our nation another 200 years and a brutal war to seriously start reforming the huge problem of slavery.

Which testimony is most important (Simplicity, Peace, Integrity, Community, Equality, Stewardship)? Fox put peace ahead of equality. Yet, without the shared equality of consensus, we will never have sustainable peace, as majority rules and unequal power creates divisions and abuses. The root problem with capitalism is putting money as master ahead of God’s equal love creating selfish motives to exploit others for personal gain. The solution is starting with most churches still using the force of majority rules and shifting to Jesus’ model of voluntary consensus and spiritual unity to lead our governments to a better example of shared power.

I want to believe that the “Peace testimony” is actually a return to “primitive Christianity.” Perhaps you are right that it was also a means of survival, though that seems to make Fox and other Friends out to be dishonest, as they portray their pacifism as a result of following Christ, not cowering away from martyrdom.

What were Friends doing in Barbados? Were they building their wealth through the theft of other peoples labour? I suppose the rebellion charge is that if the human beings that were enslaved by Quakers and others could be shown to be fit to join in worship, they might start to demand other rights as well. But again, what were these Quakers doing in Barbados to begin with?

The testimonies are an invention of Howard Brinton, who believed in the superiority of white civilization of which he deemed Quakers to be the ultimate expression of. As far as consensus decision making, many Indigenous Peoples held that practice long before the existence of the Quaker religion. Friends worked to eradicate such practices. Brinton writes in his book “Friends for 300 Years” the racist notion that consensus decision making appears at what he feels is the most inferior stage of human development (Indigenous matriarchal cultures) and at what he sees as humanities highest stage (Quakerism). He reasons that human beings must pass through an intermediary stage where “voting” appears (a justification for the genocides Quakers promoted and participated in). Voting made it easier for Quakers to eradicate Indigenous Peoples cultures, as it is easier to push through radical changes to a community if you only need 51 votes out of 100, mixed with the constant message that unless Indigenous Peoples gave up their cultures, they would all soon be dead.

Yes. In Barbados, Quakers were building up wealth by stealing other people’s labor and harming their bodies. According to Helena Cobban in Just World News, Quaker involvement in slavery began in Barbados in the 1600s.

Quaker enslavers amassed money in Barbados by stealing people’s lives. Sugar cane production on the island started in 1637. Enslaved people cultivated sugar as well as tobacco, cotton, ginger, and indigo. Three years later, when Brazil’s sugar industry collapsed, the people in power in Barbados switched entirely to producing sugar. This began a 40-year period of incredible wealth for landowners in Barbados, all of it stolen.

In 1655, Ann Austin and Mary Fisher, both Quaker, visited Barbados. Their purpose was to convert people to Quakerism. According to Katharine Gerbner in the book Christian Slavery: “Their first converts included slave-owning planters, merchants, indentured servants, and craftsmen.” As far as I am aware, they did not challenge the practice of enslaving people.

By at least 1657, George Fox was aware that Quakers were enslaving people outside of England. He wrote an epistle that year which he addressed “To Friends Beyond the Sea, That Have Blacks and Indian Slaves.” In it, he mostly quotes the Bible and offers encouragement. He does not send a reproach. To read that epistle:

http://articles.ochristian.com/article4056.shtml

To read more of the historical context, see Helena Cobban’s blog post about George Fox’s visit to Barbados:

https://justworldnews.org/2021/05/31/1671-quaker-leader-george-fox-in-barbados

There is a power to someone expressing the words “George Fox was a racist” that is liberating. I am sure most Friends will ignore this article, but it still means something that it was written and that it was published.

How often have Quakers over the years read the words of Quakers before them and pretended not to see what is so plain: the white supremacist ideology. That is what was so surprising to me reading some of the old documents, just how confident Friends were in their own sense of superiority and the superiority of the white race and white religion. All of which is a total betrayal of the Christ they say they believed in. Surprising because so many Friends still believe in “Quaker exceptionalism,” which seems very similar to white exceptionalism. Perhaps this is why many Friends still cannot handle any criticism, even criticism towards Quakers who are long dead. White exceptionalism/pride goes hand in hand with fragility.

Then coming to the present, that this history has been forgotten. Another crime!

This history is essential in understanding this religion and yet few Friends have any interest.

One specific comment about the article: When the Yearly Meetings of Turtle Island (aka North America) and Britain Yearly Meeting were working to eradicate Indigenous Peoples cultures (languages, spiritualities, scientific/ecological knowledge, women’s rights), they were doing so to secure and expand their own stolen wealth and aid the white race in total domination over the continent. The call was coming loud then for total extermination (mass killing). Friends thought that Indigenous Peoples could be pacified through cultural erasure, saving the white race from the supposed necessity (and expense) of the total extermination of the Indigenous Peoples.

White saviours indeed.

Thank you for your research into the truth. So often narratives are changed and the realities are suppressed by mainstream historians and educators. When this happens – as it does in colonized countries, and under Empires that consist of one group of people dominating another, we perpetrate the damage that was originally wrought. Denial leads to ignorance and ignorance allows for harm to be perpetrated.

The slaves were never compensated. Their ‘owners’ were. Yet the word owner is a fallacy, a travesty. When we learn the real history we have a chance to go forward differently, and only with that pure truth can the spirit move and guide us. The spirit cannot move in contaminated waters. Thank you again for your brave good work.

I wish to acknowledge the remarkable research done by Johanna Jackson and Noveed Moeed in their article printed here with the enlightening contribution to Quaker Friends understanding of George Fox as a “Racist,” which in my best thinking adds to creating an acceptance of how we are all flawed even within our sense of having “Quaker exceptionalism’ as though somehow this makes those of us identified as a friend above the common person. Likely Fox was a product of his environment as we all are without considerable reflection and willingness to stand up for what we recognize and see as flawed. I felt after some years of attending meetings at the wonderful Berkeley Friends Meeting at Vine and Walnut that there was an implicit, silent agreement in place to not give voice to mine and some others uncomfortable experience of sexism existing within the Meeting House. I addressed my having these expereinces with a few members and realized my grievance was not understood or addressed for what it was. I would have been encouraged if this grievance had been addressed and a committee formed to air it’s painful expression and roots. My heartfelt gratitude to those who speak the plain truth and stand for freedom from oppression for everyone. What was once history need not be repeated.