Strong Female Leadership in the Early Days of Quakerism

A few months ago my wife and I poured over Elsa F. Glines’s Undaunted Zeal: The Letters of Margaret Fell, published in 2003 by Friends United Press. Each evening for weeks, we were immersed in the unedited, raw 1600s language of this remarkable Quaker elder. Reading her words of encouragement to imprisoned Quakers, like George Fox, laced with biblical references and bold admonitions to hold to “the Measure of God” within changed both of our understandings of what early Quakers faced.

On the quatercentenary of George Fox’s birth, I want to articulate the yoked spiritual legacy of George and Margaret Fell Fox, who married in 1669. This seems to me to be the holistic approach to Fox’s life and legacy, for he did not journey alone. His partnership with Margaret meant the world to him, shaped his thought, and had a profound impact on the development of the Religious Society of Friends. George and Margaret represent the origin of the river called Quakerism.

What are the main points of this legacy? If George and Margaret are our spiritual forbearers (and they certainly are my spiritual elders), what did they put into motion that makes Quakerism unique? What did they put into motion that continues to touch us in life-giving ways today? And what are the Foxes’ essential contributions to Protestant discourse?

First, I want to point out something that is often overlooked, namely that George would not have been anywhere near as influential as he was without his longtime relationship and eventual marriage to Margaret Fell. This spiritual marriage uniquely molded early Quakerism.

Margaret was landed gentry whose first husband was a distinguished judge, Thomas Fell. She penned letters to dignitaries throughout England. Her pen pals included William Penn, Oliver Cromwell, Colonel William West, Justice Anthony Pearson, and King Charles II, to name a few. George, on the other hand, came from the merchant class. He had been a shepherd before founding the Society of Friends.

From their very first meeting, Margaret knew there was something special about George and the Light of Christ that was working through him, and she desired to be part of this movement. In her first surviving letter to George in 1652, included in Undaunted Zeal, she writes, “Our dear Father in the Lord, for though we have ten thousand Instructors in Christ, yet have not many fathers for Christ Jesus that have begotten us through the Gospel.” The way George preached spoke to Margaret, and from that first meeting onward she became his staunchest supporter.

Theirs became an equal partnership across divisions of class, beginning the legacy of strong female leadership among Friends that continues to the present day. This is historically significant and unique by comparison to the origins of other European and American religions, which are patriarchal, with very few exceptions. From Margaret Fell Fox to Hannah Whitall Smith to Gene Knudsen Hoffman, Mary Dyer, Alice Paul, the Grimké sisters, Sarah Mapps Douglass, and so many more, Quakerism has produced more strong female leaders per capita than any other Protestant denomination.

George would not have been anywhere near as influential as he was without his longtime relationship and eventual marriage to Margaret Fell. This spiritual marriage uniquely molded early Quakerism.

In 1660, England was moving out of its Civil War; King Charles II was restored to the throne, and Margaret was a widow. With Judge Fell’s passing in 1658, George was not protected from the law as well as he once was. Then, in the summer of 1660, George was imprisoned in Lancaster Castle on questionable charges of insurrection against Charles II.

In one of Margaret’s letters to George from that summer, she writes, “All is very well here. And all the Meetings full and quiet.” She eases George’s mind about the meetings for worship, which were going on in his absence, after previously telling him of her exploits to get a paper she had written and a book George wrote into the King’s household. While in London, Margaret tirelessly petitioned on George’s behalf. Her strong networking leadership behind the scenes cannot be overstated. Without it, George would have fared far worse at the hands of English magistrates.

Their relationship was no top-down, inequitable relationship, which was the norm of male-female relationships of the time. Theirs was an egalitarian relationship that affirmed two heads are always better than one when thinking a problem through to resolution. The two valued dialogue and process over expediency.

George wrote to Margaret in 1674 asking if she would pay some money to the meeting in Westmorland, as he could not do it himself, but he told her to do it “according to [her] time and word,” as recounted in Henry J. Cadbury’s 1962 article “George Fox to Margaret Fox.” Their relationship was cooperative: valuing the input of the other and leaving room for improvisation along the way.

It was not only times of trial, life on the road, or problems with England or other religious leaders that Margaret and George wrote to each other about. They wrote of their relationship and their love for each other, bound in the grace of their calling. In a letter to George in the summer of 1678, Margaret acknowledged their love and her longing to see him again, “but we all must submit to the Lord’s will and time.” She tells George that his “company would be more and better to us than all the world, or that all the earth can afford.” Yet she knows that his work preaching and promoting Quaker ideals was more important than her longing for his company.

They both desired that George spread the gospel and the Light wherever he could, but their calling to ministry took a toll on George, as he missed Margaret and the comforts of home. Their marriage would last 22 years until George’s death in 1691.

Unfortunately, the surviving letters between George and Margaret are few. The ones that do survive illustrate that Margaret and George conferred with each other as much as they could before making decisions. After Margaret and Anne Curtis failed to trade Anne for George in a Lancaster prison swap in July 1660, Margaret sought George’s counsel about further measures to be made to King Charles II, as she feared that once she left London it would be some time before she could come back again and petition on George’s behalf. She wrote, “[L]et me hear from thee . . . and weigh the thing, for I am given up to the will and service of the Lord.”

Margaret was, through her articles, letters, and activism, the most outspoken early advocate of Quakerism far and wide.

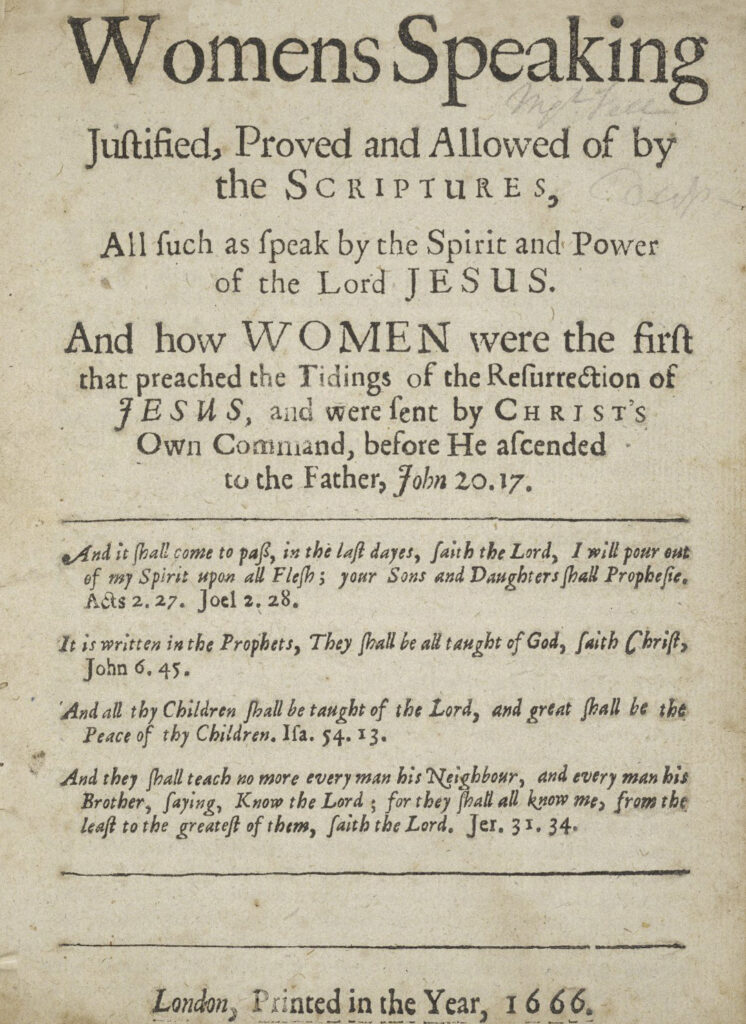

It was not just in writing letters to friends, to those imprisoned, or to petition for the Quaker cause that Margaret excelled. Both Margaret and George wrote extensively on doctrine, with Margaret’s most famous contributions being A Declaration and an Information from Us the People of God Called Quakers (1660), A Perfect Tryal by the Scriptures (1667), and Womens Speaking Justified (1666, with a second edition in 1667).

Margaret was an early advocate for women’s rights, which inspired the heavy Quaker participation in the women’s suffrage movement in the United States in the nineteenth century. She was also, through her articles, letters, and activism, the most outspoken early advocate of Quakerism far and wide. While Margaret was promoting the faith, George was the rock, the foundation, upon which the faith stood.

People who knew George best, like William Penn in an introduction to Fox’s Journal, said he “excelled at prayer” above all. He was above all a person of prayer, and Margaret was his equal, as well as a tireless advocate for both him and the new movement.

Friends are people who aspire to an interior life rooted in collective disciplined silences of meetings for worship on First Day, and perhaps in individual disciplined silences during the week. This contemplative life connects present-day Friends to their purpose and mission as members of a radical faith that can be traced back to our Society’s earliest leaders, George Fox and Margaret Fell Fox, who both gravitated toward interiority and contemplation, leading to numerous robust and active missions.

George and Margaret and the early Quakers began a river of faith and practice that has run for almost 375 years. On the four-hundredth anniversary of the birthday of George Fox, I honor their legacy and the depth of their marriage. George leaned toward prayer, preaching, and the planting of meetings. Margaret leaned toward advocacy of Quakers and Quakerism far and wide among the dignitaries of their time, and among the common people through visitation, tracts, and articles. Together they were a dynamic duo of contemplation and action.

Thanks so much Smith. I have learned alot.

Blessings.

Thanks George. Glad you liked the article.

Friends Journal gave a balanced treatment of George’s 400th. I liked the various articles this month.

Amos Smith