The Lenape People, Quakers, and Peace in the Seventeenth Century

In 1682, a group of Friends and Lenape people gathered at the deathbed of the Lenape leader Ockanickon in Burlington, in the colony of West New Jersey. One of the Quakers, John Cripps, described the scene in his promotional tract A True Account of the Dying Words of Ockanickon (London, 1682). He intended to revive interest in West Jersey immigration, which had lagged since William Penn’s founding of Pennsylvania the year prior. Cripps assured English Friends that peace prevailed in the colony despite the destruction of Lenape towns by settlement and epidemic disease. According to Cripps, Ockanickon instructed his intended heir to maintain peace with the Christians: “to keep good company, and to refuse that which is evil.”

This and other narratives became part of West Jersey’s mythology, like the legendary treaty of William Penn with the Lenape people at Shackamaxon in Pennsylvania, depicted in Benjamin West’s Penn’s Treaty with the Indians (1771–72). West’s painting perpetuated the creation story that Penn and his Quaker colleagues initiated a culture of peace in the Delaware Valley, suggesting that the Lenape people yielded their homeland from weakness and subservience to the dominant Friends.

In fact, during the seventeenth century, the Lenape (or Unami) people controlled the southern part of Lenapehoking, from Cape Henlopen (Delaware) through what became southern New Jersey and eastern Pennsylvania. They were closely allied with the Munsee people, the Lenape communities whose homeland encompassed northern New Jersey and southern New York.

In his 1670 map, Augustine Herrman marked with drawings of wigwams the location of Lenape communities such as the Cohanzick, Armewamese, and Rancocas people. He emphasized that much of southern New Jersey was still Lenape country with a statement in the lower right: “New Jarsy pars at present inhabited only or most by Indians.” Lenape people continue to live in the Lenape homeland in the twenty-first century, for example the Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape Tribal Nation is headquartered in Cohanzick territory, in Bridgeton and Fairton in Cumberland County.

During the seventeenth century, the Lenape people remained dominant in the southern Delaware Valley, though their numbers declined because of epidemics from European diseases such as smallpox, influenza, and measles. The Lenape population fell from at least 8,000 in 1600 to about 3,000 in 1670. They held significant power through alliances with the Swedes, Finns, and other Europeans who came to the Delaware Valley before the Quakers, and through the Lenape peoples’ willingness to use force to protect their homeland.

The Lenape people lived along streams in autonomous towns, which lacked palisades because they strove for peace with other nations. They had no central government that linked communities together, but the towns did ally for diplomacy and war. Their society was matrilineal, with equal status for men and women. Though most leaders were men, some women served in that role. Lenape people protected personal liberty for men, women, and children, opposing enslavement and forced adoption for themselves and others. As part of their culture of freedom, they believed in religious liberty and respect for people of other cultures.

Reciprocity was central to the Lenape economy and culture. When Lenape leaders made treaties regarding land, they expected to continue to live there, plant, hunt, and fish. When we talk about deeds or land conveyances, we are discussing treaty documents in which Lenape leaders allowed European colonists to settle and take advantage of the land’s bounty in return for trade goods and friendship. If conflict arose with the Europeans or other Indigenous people, Lenape people sought peaceful resolution when possible but used violence or threat of violence when necessary.

Two models of colonization evolved in eastern North America before 1700. In one, which developed in the Delaware Valley, the Dutch, Swedes, and Finns quickly accepted the sovereignty of the Lenape people and their expectation that the Europeans would share land and resources. The second was the plantation regime of colonies such as Massachusetts and Virginia in which European settlers used military power to force Indigenous people from their homelands. Many of the West Jersey and Pennsylvania Quaker colonists adopted a version of the plantation model in which they densely settled the Lenape homeland. They shunned military force but took advantage of Lenape population decline to push those communities from prime agricultural territory.

These two models developed from the arrival of Dutch traders circa 1615. The Dutch initially focused on trade, but in 1631 attempted to establish a plantation settlement at Cape Henlopen (with plans for Cape May as well). The Sickoneysinck people, a Lenape community, destroyed the Swanendael plantation and killed all 32 residents. The Dutch and Sickoneysinck people had different understandings of their treaty agreement. The Dutch incorrectly claimed that they had bought a broad expanse of land along Delaware Bay, while the Lenape people had agreed only to provide space for a trading post and adjacent farm. In early 1633, Sickoneysinck leaders reached peace with the Dutch captain David de Vries, and trade resumed. With their attack on Swanendael, the Lenape people successfully prevented until the 1680s large-scale colonization such as in New England and Virginia.

In 1638, when the New Sweden company sent ships to establish a colony in the Delaware Valley, the Lenape people welcomed additional opportunities for trade. Despite some initial conflict, the Lenape people, Swedes, and Finns created a long-lasting alliance that was unique in North America. Individuals had already formed personal relationships by the time Governor Johan Risingh arrived from Sweden in 1654, when Lenape leaders and Risingh established a formal alliance. Risingh promised the Lenape leaders that the Swedes “wished to damage neither their people nor their plantations and possessions.” He suggested a mutual pact in which they would disregard rumors of “bad intentions.” Similarly, the Lenape leader Naaman pledged that if they heard of plans for an enemy attack, they would inform the Swedes “even in the middle of the night.”

Lenape leaders demonstrated their commitment to the alliance in 1655 when they warned of Dutch plans to assault New Sweden. Dutch troops defeated the Swedes and Finns, and damaged a great deal of property but left the Swedish and Finnish community intact. As neighbors with Lenape communities, the Swedes and Finns established relatively small farms, shared common lands, pursued the fur trade with Native people from the Atlantic shore to Maryland and Pennsylvania, and served as interpreters for the English colonists.

The alliance remained firm through the seventeenth century and beyond, as the Swedish Lutheran priests Andreas Rudman and Ericus Björk wrote in a 1697 letter to the Swedish ambassador in London that the Lenape people, Swedes, and Finns “live together in the most friendly manner, in trade, in council and justice.” Roaming livestock was a major issue that the Lenape people and Delaware Valley colonists resolved through negotiation, unlike other colonies such as Massachusetts and Virginia where colonists used conflict over livestock as justification for war.

When the Friends began arriving in 1675 to establish Salem and West New Jersey on the east bank of the Delaware River and Pennsylvania on the west bank, they entered a region dominated by the Lenape people in alliance with Swedish and Finnish colonists. These earlier European colonists had learned to share the land, not try to force the Lenape people out of Lenapehoking. The Quakers considered the region attractive for its promise of freedom from the religious persecution they suffered in England and for its wealth of resources, arable land, and commercial opportunities.

The Friends knew that wars had erupted for decades between European settlers and Indigenous nations in eastern North America. In 1675–76, when Quaker settlement began, English colonies north and south of the Delaware Valley—in New England and the Chesapeake—brutally usurped Native homelands. George Fox and other missionaries who had traveled in Lenapehoking several years earlier told prospective settlers that the Lenape people were strong and committed to their own religion, yet courteous and generous to those who came in peace. The West Jersey proprietors and William Penn set up governments without militias or fortifications and, following the lead of Lenape people and earlier European settlers, negotiated to resolve conflicts peacefully.

Even so, Quaker colonization in southern Lenapehoking resulted in disruption of Lenape communities and expropriation of land. By 1700, when European colonists numbered 3,500 in West Jersey and 18,000 in Pennsylvania, Quaker settlers took advantage of Lenape population decline to settle densely rather than share the territory with their Indigenous hosts.

Of the Quaker founders, only John Fenwick in 1675–76 acknowledged Lenape control in a major treaty, perhaps because the Cohanzick community outnumbered the Salem colonists. The Cohanzick leaders demonstrated their negotiating strength in several treaty documents by requiring an exception for lands on which they lived. The document for Salem River to Stow Creek, for example, “excepted always . . . the plantations in which [the Cohanzick people] now inhabit.”

When 230 West Jersey settlers landed in 1677 on the ship Kent, they obtained assistance from Lenape towns and the Swedes and Finns at Raccoon Creek, now Swedesboro. The Lenape people debated how to greet these new arrivals, considering the waves of disease that came with earlier groups of European immigrants. According to Quaker Thomas Budd’s report of several conferences, young Lenape men pressed for war. The Lenape leaders “were advised to make war on us and cut us off whilst we were but few, and said, they were told, that we sold them the smallpox” along with trade goods.

The Lenape leaders promised the Friends that they would not attack, and expressed their expectation to share resources and land, stating:

You are our brothers, and we are willing to live like brothers with you: We are willing to have a broad path for you and us to walk in, and if an Indian is asleep in this path, the Englishman shall pass him by, and do him no harm; and if an Englishman is asleep in this path, the Indian shall pass him by, and say, he is an Englishman, he is asleep, let him alone, he loves to sleep.

The Lenape people offered to share their land with the Quaker immigrants as they had with the Swedes and Finns, but like colonists in other parts of North America, the West Jersey proprietors and William Penn wanted a separate path of colonization, with sole ownership of the land.

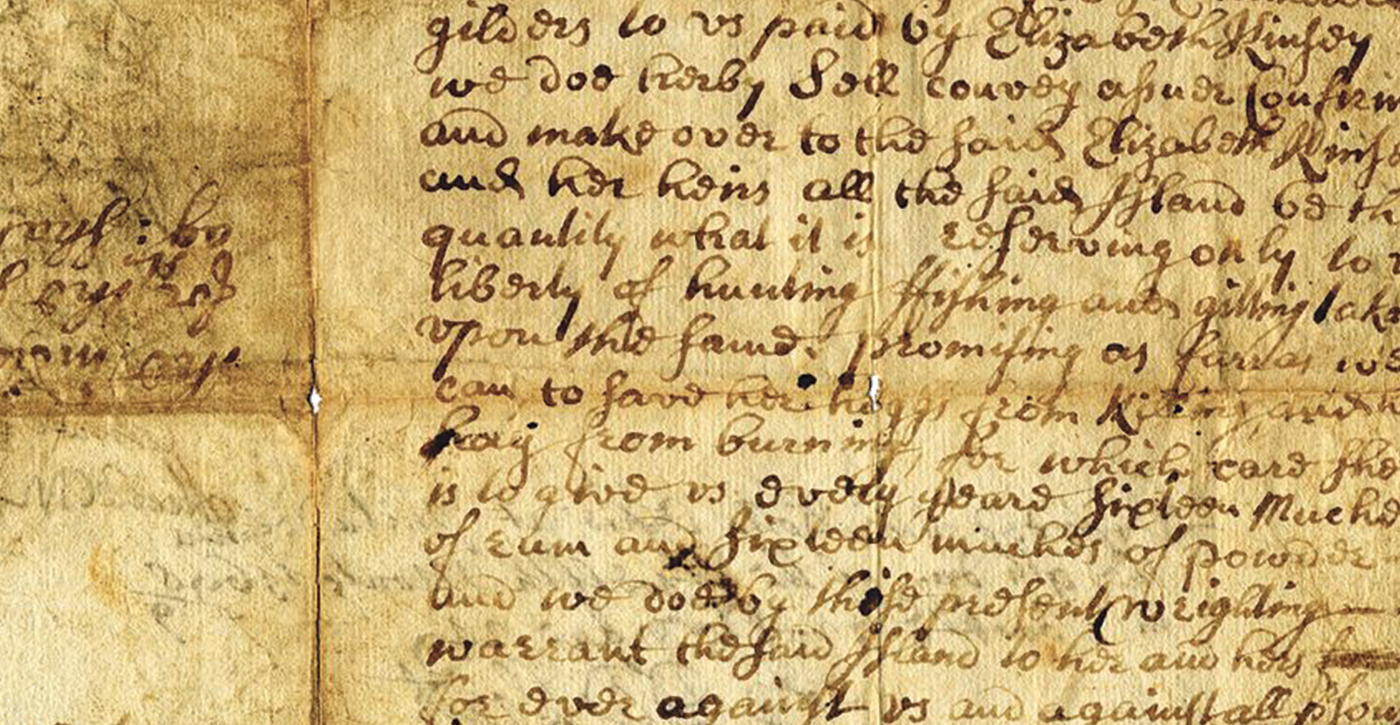

The West Jersey proprietors and Penn’s government negotiated for large expanses of prime Lenape territory on both sides of the Delaware River. A close look at a 1678 treaty document provides insight into the expectations of Lenape people in permitting settlement on their land. A young Quaker woman, Elizabeth Kinsey, and four Lenape leaders negotiated over rights to Petty Island, then called “the great island” on the Delaware adjacent to Shackamaxon, where Philadelphia is now located. The treaty document gave Kinsey use of the island for the approximate equivalent of about $4,000 (in 2024 currency) while Lenape people would continue to hunt, fish, and dig for tuckahoe, an edible root. Kinsey also agreed to provide them annually with a small amount of rum and gunpowder in return for protecting her hogs from being killed and her hay from being burned.

Many, perhaps most, Quaker colonists of West Jersey and Pennsylvania assumed that the Lenape people transferred full ownership with rights to carve up the meadows and forests into farms and towns. For Friends, epidemics apparently smoothed the way, as God brought plagues to help the newcomers. For example, in 1676, Quaker Robert Wade wrote to his wife, Lydia, that God favored Quaker colonization as it proceeded without military force:

In New England they are at wars with the Indians, and the news is, they have cut off a great many of them; but in this place, the Lord is making way to exalt his name and truth; for it is said by those that live here abouts, that within these few years here were five Indians for one now.

In 1680, Quaker Mahlon Stacy asserted that “the God of Life abounds in His love to His little flock, daily extending His peace (as a river) to His remnant.” Stacy was convinced that the colony would have an impressive future because the Lord “was removing the heathen that know Him not, and making room for a better people, that fears his name.”

As epidemics raged and colonists settled densely, the Lenape communities gradually moved upstream to the heads of creeks in southern New Jersey and farther west in Pennsylvania. A dispute in New Jersey in 1703 demonstrated how Quaker colonists and Lenape leaders kept peace despite serious conflicts over land. By that year, the Lenape people decided colonization had gone too far, threatening their towns at the heads of streams. The leader Mechmiquon contacted the Council of West Jersey Proprietors, whose purpose was to obtain Lenape land and oversee its distribution. Mechmiquon reminded the council that Lenape leaders had personally marked the border with the colonists, who accepted it as the “Indian Line.” The council admitted the mistake, helping to preserve several Lenape towns, yet colonization continued after this year.

It perhaps seems harsh to conclude that Quaker colonization in West Jersey and Pennsylvania, which proceeded without war in the seventeenth century, was quite similar in its results to colonization in places such as New England and Virginia where colonists used military action to destroy Native towns. In the Delaware Valley, pacifist Quakers praised God for destroying Lenape people with disease, then occupied their land.

Prior to the arrival of Quaker colonists, the Lenape people, Swedes, and Finns had formed an alliance to avoid war. The Lenape sachems (chiefs) offered an intentional peace, one that welcomed coexistence, not just the absence of war and militarization. The Lenape leader had said to the Quaker colonists: “You are our brothers, and we are willing to live like brothers with you: We are willing to have a broad path for you and us to walk in.” While the West Jersey and Pennsylvania colonists wanted sole ownership of the land, the Lenape people intended to share their homeland with the European immigrants, and, in fact, continue to live in the Delaware Valley.

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.